Processes

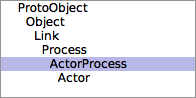

Each Actor is a Smalltalk Process. There are two important subclasses

of Process:

Each Actor is a Smalltalk Process. There are two important subclasses

of Process: ActorProcess, which implements a subset of the Erlang

process model; and Actor, which goes a step further, adding a

convention for using Message objects for RPC and using ordinary

objects as actor behaviors.

Most programs will use Actor

rather than ActorProcess.

No process isolation is implemented. This is a big difference from languages like Erlang. All Smalltalk objects coexist in a single mutable shared heap. This means that it is very easy to accidentally pass mutable objects between actors. See below.

Actor: Concurrent Smalltalk objects

Every Actor’s behavior is specified by a distinct

behavior object, usually (but not always!) a

subclass of ActorBehavior.

Because Actor is a subclass of both ActorProcess and Process, it

inherits the public interfaces of both. See

the section on ActorProcess

below for details.

Creating Actors

ActorBehavior subclass: #SimpleTestActor

instanceVariableNames: ''

classVariableNames: ''

poolDictionaries: ''

category: 'Actors-Tests'.

a := SimpleTestActor spawn.

"an ActorProxy for an Actor (92060) on a SimpleTestActor"

a := Actor bootProxy: [ SimpleTestActor new ].

"Equivalent to the previous line"

Actors are created with Actor class >> #boot: and friends, or with

the convenience method ActorBehavior class >> #spawn, if the desired

behavior object is an ActorBehavior.

If boot: is used, the result is a (running) Actor instance.

If spawn (or Actor class >> #bootProxy:) is used, the result is an

ActorProxy instance, which automatically performs many of the parts

of the RPC protocol that Actor instances expect. See the section on

proxies.

See below for a complete list of available constructors.

Sending requests

Given an ActorProxy for an Actor, requests can be sent with

ordinary message syntax. They are handled by methods on the behavior

object. In this example, a’s behavior object is a SimpleTestActor,

which has the following method on it:

SimpleTestActor >> addOneTo: aNumber

^ aNumber + 1

This allows us to send requests like this:

a addOneTo: 1. "a Promise"

(a addOneTo: 1) wait. "2"

By default, requests will be synchronous, yielding a promise for the eventual result.

The ActorProxy methods async, sync or blocking select

alternative behaviors:

a async addOneTo: 1. "nil"

a sync addOneTo: 1. "a Promise" "(like the default)"

a blocking addOneTo: 1. "2"

See the section on interaction patterns for more information on why and when you might want to use each of these variations.

Under the covers, a proxy builds an ActorRequest

instance and sends it as a message to the proxy’s actor. If programs

directly use Actor >> #sendMessage:, they must do the same.

Of course, any uncaught exception from the behavior object causes immediate, permanent termination of the actor, and rejection of all outstanding and future requests.

Given the following method:

SimpleTestActor >> divideOneBy: aNumber

^ 1 / aNumber

The following request will cause a to crash:

a divideOneBy: 0. "a Promise"

The resulting promise will be rejected, with an ActorTerminated

bearing the ZeroDivide exception as an error value. All subsequent

requests to the now-dead actor will also be rejected with a similar

ActorTerminated object. See the section on

error handling for more details.

If the promise is waited for, the ActorTerminated exception will be

signalled:

(a divideOneBy: 0) wait. "Signals ActorTerminated"

a blocking divideOneBy: 0. "Signals ActorTerminated"

Implementing a behavior

Behaviors must take care to distinguish between three important objects:

-

selfis the behavior object, whose methods are invoked by its correspondingActorinstance. -

Actor currentis the currently-executingActorinstance. -

Actor meis anActorProxyfor the currently-executingActor.

A behavior may freely invoke methods on self, but must take care

when performing RPC using ActorProxy >> #blocking or Promise >>

#wait, lest it deadlock: while an actor is blocked, waiting for a

reply to an RPC request, it does not process incoming requests.

If a method on a behavior object returns self, the request that led

to the method call is answered with Actor me in place of the

behavior object. No other translation of request messages, reply

messages, or exception values takes place as they travel back and

forth between actors. See the section on

weaknesses for more information.

Terminating an actor

An actor’s behavior object may perform a “normal” exit via

Actor current terminate.

This terminates the currently-executing actor with nil as an

exit reason. Alternatively, any uncaught

exception terminates the actor abnormally with the exception as its

exit reason:

Actor current kill. "Terminates with a generic exception."

self error: 'Oh no!'. "Any other exception will work."

1 / 0. "Ordinary exceptions do the same kind of thing."

Whenever an actor terminates for any reason, normally or abnormally, all its outstanding requests are rejected, as are any requests that may be sent to it in future.

An actor may be terminated from the outside, as well: if an actor

holds p, an ActorProxy for another actor, it can cause the other

actor to terminate abnormally by executing

p actor kill.

Note that kill is a method on Actor, not a method on p’s

behavior object. See the section on proxies for more

information on the actor method of ActorProxy.

Cleaning up associated resources

If an actor’s behavior object responds to postExitCleanup:, that

method is called after the actor has terminated. The argument passed

to the method is the exitReason of the terminating actor.

The method runs in a fresh, temporary process, not in the actor’s own

process. By the time of the call to postExitCleanup:, the actor’s

own process is guaranteed to have terminated. See ActorProcess >>

signalExit.

ActorProcess: Erlang-style processes

Instances of ActorProcess implement a “process style” actor, in the

terminology of

De Koster et al..

Specifically, they implement a subset of the Erlang approach to the

actor model, providing

- a main process routine;

- a “receive” operation;

- a form of selective receive;

- distinct system-level and user-level messages; and

- Erlang-style “links” and “monitors”.

They are more general than Actor instances, in that they do not

enforce any particular convention for the user-level messages

exchanged by the actor. However, they are awkward to use directly.

It is almost always better to use Actor with a custom

ActorBehavior object instead of using ActorProcess directly.

The main process routine

A plain ActorProcess (as opposed to an Actor) is started with

ActorProcess class >> #boot: and friends:

a := ActorProcess boot: [ "... code ..."

msg := ActorProcess receiveNext.

"... more code ..." ].

a sendMessage: 'Hello!'.

Like any other Process, an ActorProcess can be terminated. Any

time an ActorProcess terminates, normally or abnormally, its

links and monitors fire, letting interested

peers know that it has died.

If an uncaught exception is signalled by the main process routine, the actor is terminated permanently. See the section on error handling for more details.

The currently-executing Actor or ActorProcess instance can be

retrieved via Actor class >> #current, and an ActorProxy for the

currently-executing actor can be retrieved via Actor class >> #me.

Actor current. "an Actor (79217) on a SimpleTestActor"

Actor me. "an ActorProxy for an Actor (79217) on a SimpleTestActor"

System-level and user-level messages

Messages exchanged among ActorProcess instances come in two kinds:

system- and user-level.

System-level messages are a private implementation detail. They manage

things like links and monitors, and a specific type of system-level

message carries user-level messages back and forth. See senders of

performInternally: to discover the types and uses of system-level

messages. System messages are comparable to (and inspired by)

Erlang’s system messages.

User-level messages are the things sent by ActorProcess >>

sendMessage: and received by ActorProcess class >> #receiveNext.

They are a public aspect of working with Actors.

Programmers design their Actors in terms of the exchange of user-level messages, and never in terms of system-level messages.

While any object can be sent as a user-level message between Actors,

the convention is that instances of ActorRequest

are the only kind of user-level message exchanged.

“Internal” and “External” protocols

Unlike ordinary Smalltalk objects, which have public methods and

private methods, ActorProcess instances have three kinds of

method:

- public, “external” methods, for use by other actors and processes;

- public, “internal” methods, for use only by the actor itself;

- and ordinary private methods, part of the actor system implementation.

External methods include sendMessage:, kill, terminate,

isActor and so on. Internal methods include receiveNext,

receiveNextOrNil:, and receiveNextTimeout:.

Actor and ActorProcess constructors

There are many different ways to start an actor.

Behavior objects

ActorBehavior spawn.

ActorBehavior spawnLink.

ActorBehavior spawnLinkName: aStringOrNil.

ActorBehavior spawnName: aStringOrNil.

These constructors first instantiate their receiver (a subclass of

ActorBehavior), and then pass the result to one of the bootProxy:

variations on class Actor.

Actors with a behavior object

Actor bootLinkProxy: aBlock.

Actor bootLinkProxy: aBlock name: aStringOrNil.

Actor bootProxy: aBlock.

Actor bootProxy: aBlock name: aStringOrNil.

These constructors produce Actors having the result of evaluating

aBlock as their behavior object. The variations with Link in the

name link the new actor to the

calling process, and if a name is supplied, it is used when printing

the actor and in the Squeak process browser.

Actor for: anObject.

Actor for: anObject link: aBoolean.

These constructors produce Actors with anObject as their behavior

object.

Erlang-style processes

ActorProcess boot: aBlock.

ActorProcess boot: aBlock link: aBoolean.

ActorProcess boot: aBlock link: aBoolean name: aStringOrNil.

ActorProcess boot: aBlock priority: anInteger link: aBoolean name: aStringOrNil.

These constructors produce actors running aBlock as their main

routine. Generally speaking, aBlock will use Actor receiveNext to

explicitly receive and handle incoming user-level messages.

If aBoolean is absent or false, the new actor will not be

linked by default to the calling

process; if it is present and true, it will be linked to the calling

process.

If a name is supplied, it is used as the Process name, which is

displayed in the Squeak process browser and anywhere that the

ActorProcess is printed.

Actor boot: aBlock.

Actor boot: aBlock link: aBoolean.

Actor boot: aBlock link: aBoolean name: aStringOrNil.

Actor boot: aBlock priority: anInteger link: aBoolean name: aStringOrNil.

Since Actor is a subclass of ActorProcess, it inherits these

methods. However, it reinterprets the meaning of aBlock: instead of

aBlock enacting the main routine of the new actor, it is expected to

return a value that will be used as the behavior object of the new

actor, and the standard Actor mainloop (Actor >> #dispatchLoop)

will be used as the main routine.

Weaknesses of the design

Smalltalk poses a number of challenges to implementation of the actor model.

As has already been mentioned, chief among them is the total lack of process isolation. This means that, if a mutable object is accessible by two or more running actors, you still end up having to worry about concurrent access to data structures, even though the actor model is supposed to eliminate this as a programming concern.

An example of a distortion induced by this problem can be seen in the

use of the copy method in ChatRoom >> #tcpServer:accepted:. When a

new user connects to the chat room, they are sent a list of the

already-connected users:

agent initialNames: present copy.

The chat room must take care to send a copy of present to the new

ChatUserAgent, because of the asynchrony in the system: if it is not

copied before being sent, it may change while in flight!

A second weakness is connected to the way a returned self is changed

to Actor me. It adds a special case for convenience, but a general

solution would ensure greater process isolation by copying (or

otherwise specially treating) mutable values.

A third weakness is that block arguments to methods invoked on an actor’s behavior are not translated, which makes custom control flow awkward. For example, consider the following snippet:

b := Actor bootProxy: [ true ].

(b ifTrue: [ 1 ] ifFalse: [2]) wait

Here, b is an Actor with a Boolean as its behavior. Invoking b

not works perfectly, but ifTrue:ifFalse: doesn’t work, signalling

NonBooleanReceiver. This example demonstrates a leak of some of the

optimization-enabling assumptions the VM makes.

A similar case occurs in the following example:

d := Actor bootProxy: [ Dictionary new ].

a async at: 1 put: 2.

a blocking removeKey: 1. "This works fine..."

a blocking removeKey: 99. "... but this kills the whole actor."

If, instead, we use removeKey:ifAbsent:, we can avoid killing the

whole actor, but at the cost of having the ifAbsent: block execute

in the wrong context. That is, if it runs, it will run in a context

where self is the Dictionary, and Actor current and Actor me

denote the actor that the client knows as d. The tutorial on

collections as behavior covers this topic

in more detail.

Perhaps, in future, a special case for wrapping block arguments in an outer block that causes the block to execute in the correct Actor’s context could be added.